The Man Who Carried

the Weight of the Game

There are men who play baseball, and there are men whose very presence makes the game larger, truer, and more worthy of the name. He was always the latter.

Out of the wide and storied American heartland, from the red-brick pavements of St. Louis where the great river bends and the summer heat shimmers off the sandlots, there came a young man of uncommon gifts and uncommon grace. He was built broad and strong as a river barge, with hands that could snare a thrown ball out of the Missouri wind and a batting eye as true as a surveyor’s line. He arrived on this earth February 23, 1929, and from the very beginning, those who knew him understood they were in the presence of something rare, a talent that the ages would not easily forget.

His mother, Emmaline, had fashioned herself into a dietician by sheer willpower and sacrifice, raising her son with the gospel of hard work, clean living, and proper nourishment for body and soul. His godfather, the Reverend Jeremiah Baker, added scripture and purpose. Between them, they shaped not merely an athlete but a man, and that fact would matter enormously in the years ahead, when the world would ask this young giant to shoulder burdens that no man ought to bear alone.

The Sandlot & the Calling

In the summer of 1945, a scout named Frank “Teannie” Edwards came upon a sandlot game in St. Louis and stopped dead in his tracks. The biggest boy on the field was lashing the ball so far and so hard that it made the old baseball man furious, furious not with the boy but with the sheer extravagance of nature to put such raw genius out there in the open dust, unclaimed and unschooled. The boy was sixteen. Edwards wanted him immediately.

Convincing his mother was the genuine contest. Teannie Edwards had to swear a solemn oath that the boy would eat properly before she relented. On Easter Sunday, 1946, the lad pulled on a catcher’s mitt and debuted in the Tandy League. He promptly stroked two hits and gunned down two baserunners trying to steal second. A career had begun. But not yet the career that would make history.

He was, at Vashon High School, a prodigy of the rarest order. Football, track, basketball: in each arena he stood apart, earning all-state honors on the hardwood, thundering down the gridiron, leaving competitors breathless at the finish line. Three Big Ten universities beckoned for his football services; others came calling for his exploits on the court and the cinder track. His mother dreamed of a physician’s white coat. The baseball diamond had other plans.

The Monarch Summers

Teannie Edwards summoned scouts from the Kansas City Monarchs, that most storied of all Negro League franchises, the very outfit that had dispatched Jackie Robinson to change the world. They came, they watched, and within days they made their offer: five hundred dollars a month, mailed directly to his mother. She accepted.

In Kansas City he found a world of kings. Buck O’Neil, that magnificent player-manager and philosopher of the game, took the young man in hand. His roommate, catcher Earl “Mickey” Taborn, showed him how to receive a pitch, how to frame a low ball, how to earn a pitcher’s trust. The Monarchs dressed in tailored clothes and dined at fine tables and listened to the finest jazz in the land. This was the Negro Leagues at its summit: brilliant, joyful, full of fire, and yet always aware that the national pastime had drawn a color line that divided it from the greater game.

He played the outfield when Taborn was behind the plate, and filled in at first when O’Neil rested. He learned the rhythms of the professional game. And somewhere in those summers of 1948, 1949, and 1950, he roomed with a gangly young shortstop from Dallas named Ernie Banks, and the two of them, both understanding that the walls were about to come down, made a gentleman’s wager: whoever reached the major leagues first would telephone the other and describe what it was like.

As it turned out, the legendary Yankees scout Tom Greenwade arrived to inspect a different Monarch altogether. But Buck O’Neil steered him purposefully toward the young catcher-outfielder. Greenwade watched, and the Yankees saw what the Monarchs had long known. For twenty-five thousand dollars, two players were purchased, and one of them was bound for a place in history.

The Long Road to the Pinstripes

It is not enough that a man be great at his craft. The world, in its imperfection, sometimes demands that he be greater still: more patient, more dignified, more resolute than the obstacles arrayed against him.

The path from Kansas City to the Bronx was not a straight one. It never is for men who must knock down doors that ought never to have been locked in the first place. He stopped first in Muskegon, Michigan, in the Class A leagues, arriving midsummer and promptly leading the Clippers on a 36-18 tear. He batted cleanup and inspired those around him. Then the Army called, as armies will, and he spent the Korean years in Japan playing baseball for Special Services. To its credit on at least this single point, the Army understood it had a ballplayer of extraordinary value on its hands.

By 1953, he was in Kansas City again, this time with the Yankees’ top farm club, the Blues. The newspapers began to take notice. Jet magazine ran the headline: “Howard May Be First Negro With Yankees.” He was the great unfinished promise, the man on the doorstep. But the Yankees were in no hurry. Bill Dickey, the Hall of Fame catcher, worked with him to make him a backstop of major league caliber. Some newspapers cried foul, arguing it was a scheme to keep him buried in the minors. Perhaps. But he mastered the position all the same.

They sent him to Toronto in 1954, to the International League, where the skies were a shade more welcoming. He rewarded them with a .330 average, 22 home runs, 109 runs batted in, and the league’s Most Valuable Player Award. He was 25 years old, with a freshly placed engagement ring on the finger of his sweetheart Arlene. The door was no longer merely unlocked. It had been blown clean off its hinges.

Breaking the Last Barrier in the Bronx

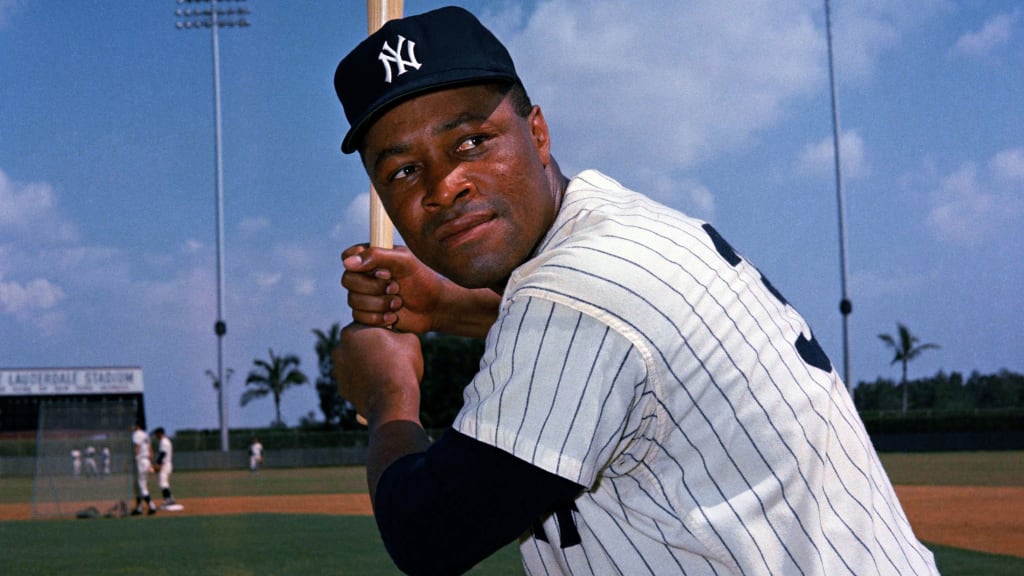

On April 14, 1955, at Fenway Park in Boston, he stepped to the plate in Yankee pinstripes for the very first time. He collected a base hit. He knocked in a run. In the days that followed, the Yankees became, at long last, a different organization, changing their traveling hotel policy to accept their new first baseman-outfielder-catcher as a guest wherever they stayed. The Yankees, proud as ever, would do what was right when they could no longer avoid it.

He was not the first black man in baseball, for that distinction belonged to the incomparable Robinson, eight years prior. But he was the first black Yankee, and in the New York of 1955, with the Giants and Dodgers still playing in the borough, that carried the weight of something almost theological. His teammates embraced him: the catcher from the hills of West Virginia, the shortstop from the Mississippi bayou, the slugger from Oklahoma. Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Hank Bauer: these were his closest friends on the club. He hit .290 that first season, cracked a home run in his first World Series at-bat, and handled himself with the composure of a man twice his age and experience.

And yet the game still made him wait. For year upon year, with the great Berra enthroned behind the plate, he played wherever Casey Stengel required: left field, right field, first base, catcher. He played each position with a craftsman’s care. He was named to the American League All-Star team. He hit for power and for average. He played in World Series after World Series, through the grand procession of Yankee dominance in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a dynasty that passed through him like a river through its banks.

The 1958 Series & The Dive That Turned the Tide

Among all the performances of his Yankee years, let us pause at the autumn of 1958, when his heroism was cemented for all time. The Yankees were down three games to one in the World Series to the Milwaukee Braves, a situation that, for most men, heralds quiet surrender. He had dental work that very morning of Game Five. He took the field in left anyway.

In the sixth inning, with the game in the balance, he launched himself headlong across the outfield grass, took the skin off his knee and his stomach, hauled in the ball that should not have been caught, and then doubled the runner off base. It was a play that did not merely save a run but altered the entire composition of a Series. “I knew I had to get the ball,” he told reporters afterward. “I’m no outfielder. I’m a catcher, but the manager put me out there and I had to do the best I could.” Two games later, with the Series tied at three, he drove in the go-ahead run in the deciding seventh game. The Yankees won. The New York Baseball Writers gave him the Babe Ruth Award as the Series’ outstanding player. He accepted it with the quiet dignity that was his lifelong signature.

The MVP & The Peak of the Mountain

The years from 1961 through 1964 were his finest hours in the sun. Ralph Houk, the very reserve catcher his own excellence had pushed back to the minors, was now managing the club, and he finally installed the big man as primary catcher. Houk trusted him. The team trusted him. He responded with a .348 average in 1961, twenty-one home runs, and a World Series championship. He hit .313 across 150 games in 1964. And in 1963, he reached the absolute summit: .287, twenty-eight home runs, a Gold Glove for his work behind the plate, and the American League Most Valuable Player Award, the first ever received by a Black man in the junior circuit.

He stood where no man of his race had stood before, in the house that Ruth built, wearing the number that was made for him, No. 32, and he wore it like a man who understood that he was carrying something larger than himself.

The commercial world came calling. He modeled clothes in the pages of GQ magazine, the first Black man ever to do so, and endorsed oatmeal, mustard, and beer alongside his wife and family. His salary rose to sixty thousand dollars, making him among the highest-paid players in the game. He built a house in Teaneck, New Jersey, in a white neighborhood, over the protests and sabotage of those who could not accept that a man’s worth is not measured by the color of his skin. He and Arlene moved in anyway. They always did what was right.

The Impossible Dream & the Final Act

Age came for him, as it comes for all great men, in the wear of the joints and the slow dimming of the fastball’s brilliance. He was traded to the Boston Red Sox in August of 1967, the Yankees slipping into irrelevance, Boston chasing one of the most astonishing pennant races in history. The Impossible Dream summer, they called it, and he had a hand in making it come true.

He was thirty-eight years old, his elbow chronically sore, his reflexes not what they had been. But what he brought to that young Boston club could not be measured in batting averages. Reggie Smith, who played alongside him, said it plainly: “He was like a pitching coach to Lonborg and the others. No doubt Elston helped us win it. We were a young team. Our average age was twenty-six. We needed someone like Ellie to show the way. He brought the Yankee aura of winning to the Red Sox.” In one late-season moment of pure excellence, with the Sox clinging to a one-run lead and the tying run barreling toward home on a shallow fly ball, he leaped above a high throw, snared it, and swept the tag in the same fluid motion. The runner was out. Boston held. The pennant was eventually theirs.

When he returned to Yankee Stadium with the Red Sox that fall, the crowd at the House that Ruth Built rose to its feet and gave him a standing ovation. He later said it was the best ovation he ever received in his life. There is no finer tribute that can be paid to a man than for the audience that once claimed him to rise and cheer for him in his new uniform, acknowledging not a team but a man.

Legacy: The Coach, the Pioneer, the Standard

He retired from playing in October 1968 and became, the very next day, the first Black coach in the history of the American League, serving as first-base coach for the Yankees. He had hoped, as many hoped for him, that he might become the first Black manager in the game. The opportunity was dangled, whispered about, never formally offered. Frank Robinson claimed that honor in 1975, in Cleveland. History records the injustice without apology.

He coached at Yankee Stadium through 1978, a steady hand amid the chaotic brilliance of the Bronx Zoo years, the counterbalance to the fiery Billy Martin, the elder statesman in pinstripes. He sat next to the furnace of that great dynasty and kept things from burning down. He was, in those years, not merely a coach but a living connection to the heritage of Yankee excellence that the new generation was trying to reclaim.

In February 1979, his heart began to fail. That great, generous engine had driven him through the sandlots of St. Louis, the jazz-filled nights of Kansas City, the autumn theatres of the World Series, and the graffiti-marred construction site of his Teaneck home. Now a virus attacked the very muscle of it. He rested. He tried to recover. He moved into the Yankees’ front office as an assistant to George Steinbrenner, scouting talent, attending banquets, representing the proud tradition he had helped build. But the heart could not be mended. On December 14, 1980, at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, the great man was gone. He was fifty-one years old.

In 1984, the New York Yankees retired his number 32. It hangs there still, in Monument Park, alongside Ruth and Gehrig and DiMaggio and Mantle, above the outfield grass where this son of St. Louis so often stood and made the impossible play look like routine.

A man’s life is the total of his deeds. Not the accolades hung in the rafters, but the grace with which he walked through the world when the walking was hard. By that measure, few who ever pulled on a major league uniform stand taller.

He came out of the sandlots of St. Louis and the Negro Leagues of Kansas City. He played before crowds that did not always want him there. He integrated the greatest franchise in the history of American sport and won four World Series championships, nine All-Star selections, one MVP, and one Gold Glove. He endured the slow cruelty of a league that made him wait years for the position and playing time his talent plainly deserved. He built his house where lesser men told him not to build it. He carried himself, through all of it, with a dignity so complete and so quiet that it made the indignities visited upon him all the more monstrous by contrast.

There is an old belief in American sport that the measure of a champion is not taken in the good times, when the crowds are roaring and the hits come easy and the sun is bright over the stadium grass. It is taken in the moments of adversity, when every reason to quit presents itself and the man must decide who he truly is.

By that measure, the only measure that finally matters, he was among the greatest champions this game has ever known. And the game, at long last, is the better for having had him.